As a busy person, sleep often evades me because I’m running through my list of tasks for the week. Either that, or my brain has decided to remind me that in first grade, I vomited in the doorway of my classroom, so teachers had to pick up and hand children to each other in order to move them in or out. Sleep is usually at least an hour away after that memory rears its putrid head.

Sleep didn’t start evading me for darker reasons until I moved away from my family.

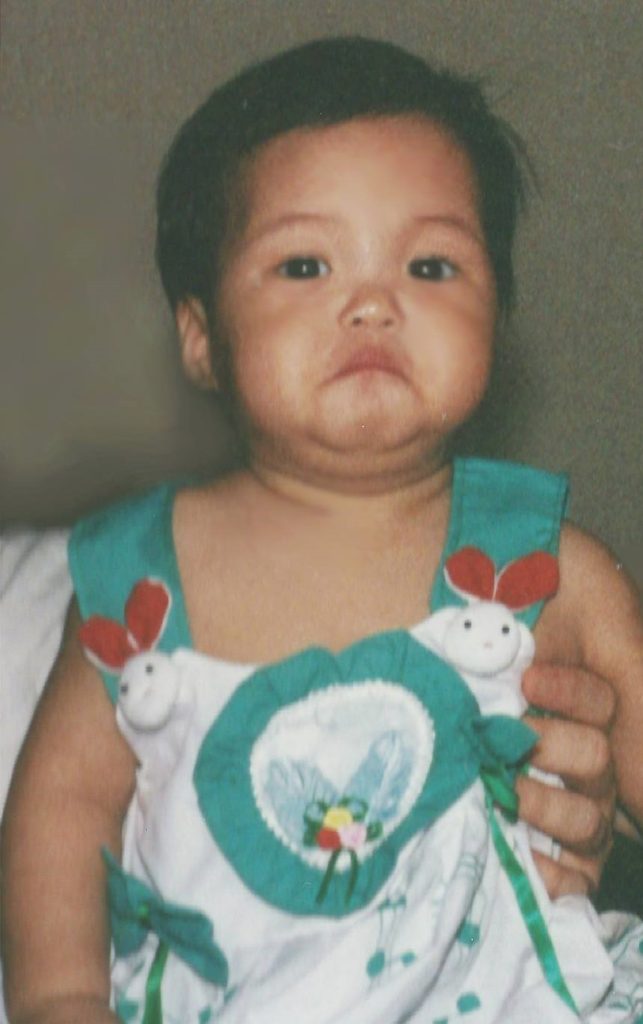

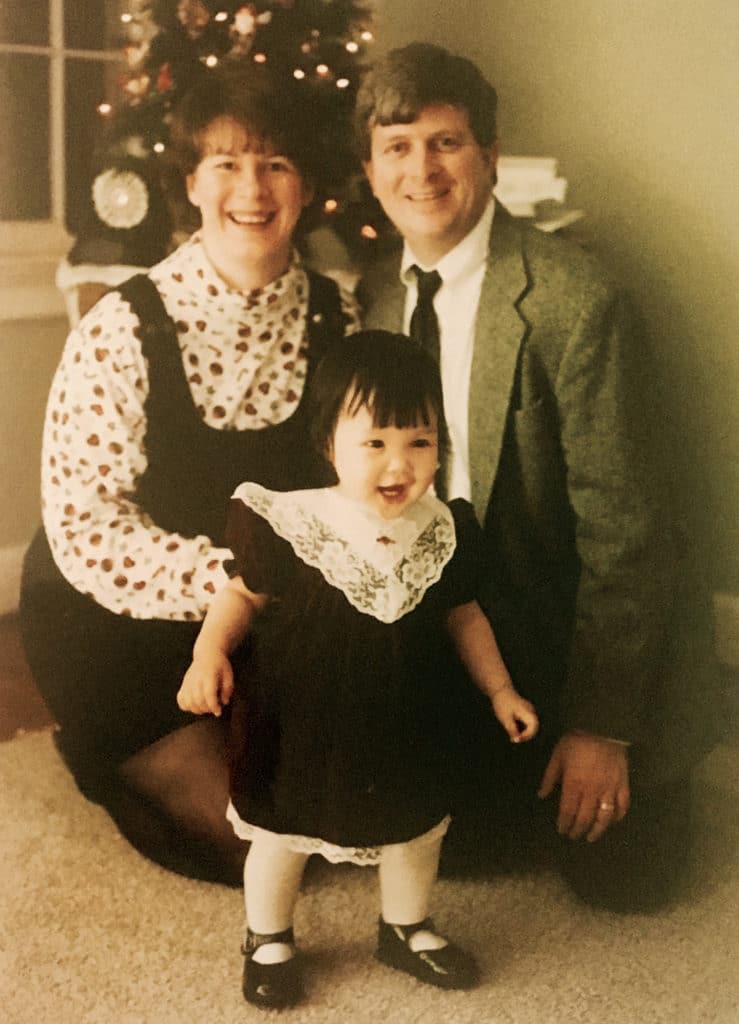

I suppose there were always signs that I might have issues. Most children who are adopted do. My parents can testify that I was a clingy kid (I prefer “overly-affectionate,” but we’ll call it what it is). When they traveled from America to meet me at the orphanage in China, I was ten months old and visibly terrified. The faded photos from that day showcase my parents, with joyous smiles and tears filling their eyes as their long journey to have a child of their own culminated, holding me, a pudgy baby whose expression resembled, most closely, a blobfish.

By the end of the week, though, I had latched onto my mother. I wouldn’t let her go to the bathroom without crawling after her. I wouldn’t let her put me down to eat dinner. There is a home video of me at fourteen months old sobbing, screaming at the top of my piercing baby lungs. Apparently, my mom had wanted her sweater that was draped over a chair on the other side of the room. I couldn’t fathom what could be more important than holding me, her only daughter, so naturally, I made that known. My grandma couldn’t satisfy me. Not even my dad (who, in the video, is seen callously chuckling at my misfortune). I didn’t stop crying until I was in my mom’s arms again, and even then, I seized her shirt in a tiny fist as if to say, don’t you dare let that happen again.

I was pretty overly-affectionate.

Even though I was adopted as an infant, the lingering effects of adoption have permeated my life. When I was in elementary school, I felt these in obvious ways, being a Chinese girl holding hands with white parents. As I grew up, I internalized these effects, and sometimes, I even tricked myself into believing that I have encountered every possible difficulty that could’ve arisen.

But living with the aftermath of adoption is an interminable journey. Being an adopted child has knocked me down in ways that I never could have anticipated.

A little over a year ago, I moved out of my parent’s house to live with my boyfriend. The first night in my new apartment, I attempted to sleep. My usual weekly tasks slipped from my mind. Not even embarrassing childhood memories made their usual guest appearance. New fears flooded my brain. This isn’t my bed. I will never sleep there again. My parents aren’t down the hall. What if something happens, and I’m not there? My dad works at the Pentagon. What if there is another 9/11? What if my mom goes to the mall tomorrow, and there is an active shooter? What if someone kidnaps my brother or sister on their walk home from school?

Alarms blared as my mind reeled uncontrollably. I was suddenly sobbing at the thought of living without my family. The dwindling, logical piece of my brain tried to reel me back in – This is irrational. You are in no present danger. – but I quickly lost that battle. A life without my family felt so catastrophic, so devastating, so real that I obsessed over my own parents’ mortality, and all emergency exits disappeared behind me.

My heart hammered against my ribs. Black clouds edged my vision, and my eyes burned as they fought the rising tears and sporadic stars that clouded my sight. My chest felt like it was collapsing on itself as I attempted to breathe. I felt consumed by an overpowering black hole of my own making. A black hole that overflowed with the fear of losing the people I loved, the people I would lie, cheat, and steal to keep safe. The fear of being alone. The fear of being without a family.

Eventually, I must have tired myself out, and my body went into an automatic shut-down mode to save itself.

The next morning, in a much clearer headspace, I convinced myself that this was a completely natural reaction to moving out. I made frequent visits home, reasoning that spending more time with my family would prove to myself that nothing was wrong. Instead, it made my fear more cognizant. Some days, I had to pull over seconds after leaving my parents’ driveway to stop shaking.

The fits at night worsened. I would work myself up to the point of hyperventilation, which instantly sparked unrelenting adrenaline. This, as you can imagine, did not help. I longed for the nights of reliving juvenile memories that I wished I could forget. Praying, counting sheep, listening to soothing nature sounds, nothing helped. More nights than I cared to count resulted in my boyfriend holding me and slowly counting to three as I tried to inhale through my nose and exhale through my mouth. When I reconnected to my physical surroundings, guilt flooded through me as I realized that this had become his problem too.

When the sun rose again, I was furious, frustrated, and tired. This is all so irrational. I am a well-adjusted adult. I have a job. I have friends and a healthy relationship. I desperately wanted to understand why I wasn’t strong enough to shake this.

The only thing I could do was learn. I learned about attachment issues that adopted children may have. I learned that I had symptoms of separation anxiety. In my college interpersonal communication class, I met another adopted girl who had the opposite problem. She had grown up without close bonds and was adopted when she was older. Now, she found it challenging to invest in friendships and romantic relationships. Whereas, I bonded very quickly and latched onto my loved ones with an iron grip.

Even children adopted as infants are instilled with deeply-rooted fears of abandonment. When I was five months old, my birth parents – who had held me, fed me, changed my diapers – left me on the side of a bridge. I never saw them again. When I was ten months old, I would never see nannies who’d cared for me at the orphanage again (hence, my blobfish face). In the first year of my life, I was growing and changing, and the instability of where I belonged and who I could depend on was constantly changing too.

I latched onto my mom because even as a child, I was afraid that she would leave. Even as I write this, though, I find myself suppressing emotion because this fear is so ridiculous. The end of the world couldn’t make my mom leave me. Amidst fire and brimstone, she would be right there to ask about my day and nag me to stop procrastinating on my taxes.

My family is my world. Separation anxiety makes me feel like my love for them is what is wrong with me. In reality, it is the deeply-ingrained misbelief that they might abandon me one day.

A year ago, I moved across the country for my career, which was one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever made. Some nights are still sleepless. Some days, I suppress tears when my boyfriend leaves for work, which is embarrassing to admit. Deep down, I worry that one day, he might not come back. Even though he always, always does. It is difficult to not get frustrated with myself because I thought I was more resilient, but the wounds of my birth parents’ abandonment always lurked, leaving me vulnerable. Not even adoption by a loving family made me feel completely secure.

My entire life, I believed that adoption was a gift, and it can be. I have a family who loves me, and I live a privileged life because of my birth parents’ heartbreaking decision. It was a rude awakening to learn that this “gift” may also be the source of my panic attacks. Adoption is loss even for people who don’t consciously understand why they are grieving. Adoption is a lifelong journey, and pieces of my past that I would rather forget will always remain with me.

I didn’t write this to invoke sympathy. I have a job that I love. I have friends and a healthy relationship. I am also fortunate to have the resources to tackle this. Wallowing in self-pity is a waste of time, and I want to address the problem, reflect, learn, and take action. I chose to share this to increase solidarity. Everyone struggles with issues unseen by others. It is easy to feel alone and isolated and accept that no one cares. It is hard to look beyond those initial feelings and seek the help that you need.

My fear still lingers, but I work through it a day at a time, which is all one can do. Every day, I call my mom, and she picks up within the first few rings. Every day, my boyfriend comes home when he says he will. Every night, I am sleeping a little easier.