I was a recent American college graduate dropped in central China with a mission. I had just started a Fulbright grant researching Student Village Officials (or SVOs), a particular group of young government officials in China who were scattered across the country working in rural villages. I needed to somehow get in touch with, and interview, them.

I made contacts through friends and friends of friends, but that covered SVOs in only two cities. My first instinct was to search online for organizational contacts. I began scouring hundreds of SVO discussion forums and websites, but soon realized it was hopeless. The phone numbers were all disconnected or rang forever. The email addresses were all “webmaster@” addresses and bounced back.

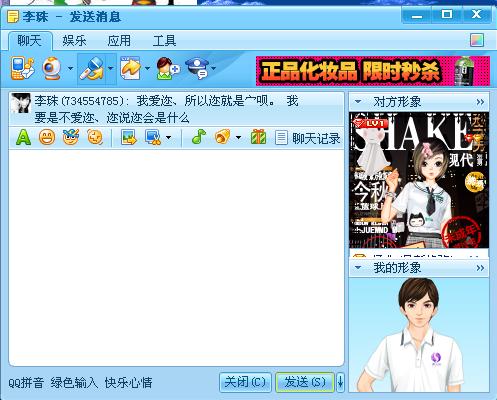

Then I discovered QQ, China’s original instant messenger. For me, “instant messenger” conjures up memories of funky fonts and colors, perfectly curated user profiles, and away messages (“brb… mom needs the comp…”). But while AIM all but disappeared and Americans moved on to Google Chat, China’s original instant message service, QQ, is more popular than ever.

With 784 million users, QQ is one of the largest virtual communities in the world, second only to Facebook. But QQ serves another purpose, one that turned my research around. QQ is also a place for work.

For SVOs who have internet access, a top priority is connecting on QQ. I soon realized that’s how they connected with co-workers during the workday and with each other. A simple search reveals over 300 ongoing group chats (QQ群) specifically for SVOs.

I joined a few to gauge interest on helping with my project. Unfortunately, I didn’t get the warm welcome I hoped. Some of the more colorful reception I received included: “We don’t like American imperialists around here,” and “This is a political plot by the U.S. government!”

Acrimony aside, this was my solution. Through QQ I met new officials, kept in touch with SVOs, even though they lived far away from my home base in Chongqing, and was able to listen in on the day-to-day commentary of SVOs from across the country.

Then came the biggest boon of my research. A girl named Pingping messaged me claiming to work at the central-level Ministry of Agriculture (MoA, one of the big three Chinese government bureaus that lead the SVO program). She said she was interested in my research and wanted to help.

I thought for sure it was a scam. Group chats frequently feature posts from scammers who jump in. (“Free iPhone 5! Please respond with your credit card information and address.”) What kind of a weirdo would stalk me on QQ?

But after talking a bit, I found out Pingping really did work for the Ministry of Agriculture. More than that, she created training materials for all SVOs and worked directly with a high-level MoA director. Pingping helped me meet with Director Zhang, who was so excited a foreigner would study her program that she wanted *my* advice on how to improve it.

What a surprise! Just three months earlier I was at a loss to make connections. By learning how QQ is used at the workplace in China, I solved my outreach challenge.

我是一个美国大学毕业生,

我想办法从朋友和朋友的朋友那里联系他们,

然后我发现了中国原创的即时通聊天软件——QQ。对我来说,“

QQ拥有7.84亿用户,是全世界最大的虚拟社区之一,

对于可以上网的大学生村官,他们的上网的第一件事就是打开QQ。

我的解决方法就是忽略这些刻薄的回复。通过QQ,

这一切马上给我的调研带来的巨大的福音。

当时我觉得这肯定是个骗局。

但是经过一些讨论,我发现萍萍真的是在农业部门工作。不仅如此,

这真是个惊喜啊!三个月前我还为谁也联系不上不知所措。