I remember the first time I saw Ma cry—because I made her. I was eight years old and as soon as the tears started to stream down her face, I was afraid that she would never love me again.

We had just moved from Beijing to Washington D.C., where my father was reassigned as a diplomat in the State Department. We had lived in Beijing for three years, where I attended a local Chinese elementary school and Mandarin had become my first language. For Ma, moving back to the U.S. meant navigating new cultural and educational territory. Without a strong Chinese program in the area, Ma was adamant that my sister and I retained our bilingual skills, so she taught us Mandarin every day after school. I hated it. Each lesson, dictation, and assignment was met with all of the resistance my third-grade self could muster. The “tiger child” in me wanted nothing more than to go outside and play with my new friends; the newly initiated “American” in me did not understand the importance of my Chinese heritage.

“If you don’t speak Chinese you’re not my daughter,” Ma said between tears one day after particularly a big fit I threw. She pushed herself up from the kitchen table and walked away.

I remember Ma’s face so clearly not only because I was shocked to witness my mother cry, but also because this was the first time that I realized how critical my Chinese identity was to my relationship with Ma. I realized at a young age that that there was something much larger at stake than passing Ma’s 听写 quizzes. If I did not speak Mandarin or lost my Chinese identity, I would lose part of Ma too.

Ma was exactly my age, 23, when she first left her homeland, China. Driven to study abroad, she taught herself English each morning before her peers woke up by memorizing English words and listening to language tapes. Little did she know she would soon pass a national exam and receive a scholarship to be one of the first Chinese exchange students to study abroad at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. That was 35 years ago. 1981. China was just beginning its process of economic cultural reform, Ma not only left her home in Shanghai for New York City, she also set off on a two-month cross-country road trip with five Chinese and Taiwanese classmates to document American life that summer.

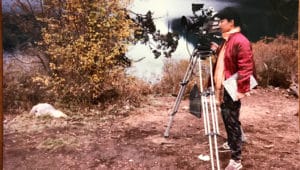

As they drove from New York to L.A., they filmed farms, factories, nursing homes, and more. Ma interviewed people from all walks of life: from writers like Studs Terkel to athletes like Mohammed Ali. She asked everyone: “what is your hope for the future?” Their answers echoed the “American Dream” at the time: to have a stable job, good health, a home, to build a better life for their children, and most importantly, happiness.

Ma describes how free and rich America seemed at the time, and how she was fueled by the same desire to create a better life. As she drove across the U.S. in a broken Cadillac, China was just stepping out from the shadows of the Cultural Revolution. When China opened its doors in the 1980s, Ma could not have anticipated the transformation that the country would undergo, let alone the profound influence history would have on her story, and that she would eventually start a family that brought East and West together.

As a stubborn teenager tiger, my aversion to learning Mandarin Chinese dismissed Ma every time she said: “you’ll thank me later.” Gratitude did not come immediately, or easily, but unfolded over time. It still comes in waves every time I am struck by the beauty of the Chinese character, my ability to converse with relatives, peers, or strangers, and when I discover another nugget about China’s rich history and vibrant culture. My gratitude grows as I find myself far from Ma, navigating a new “home” in the melting pot of New York City. I see how her determination kept the doors open for me to access both spectrums of my bicultural identity. Today, I feel the responsibility to embody and explore what it means to be Chinese is no longer on her shoulders, but on mine.