Under the backdrop of lush green, the flame in the cenotaph flickered in the gentle summer wind. Flocks of school children in uniforms sang a melody of peace. I felt a powerful serenity in the air, weighed by solemnity.

70 years have gone past. As I stood at the epicenter of the dropping of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, there was no sight of the blinding flash, the suffocating smoke, or the scorched remnants. Behind the beautiful and welcoming city, I felt the pains, saw the scars, and heard the haunting wails that once overwhelmed this site on August 6th, 1945.

As a college freshman enrolled in a class called the Advent of the Atomic Bomb, Hiroshima tops the list of historic Japanese cities, including Nagasaki and Kyoto that I had the chance to survey and study.

During class sessions back on campus, we explored the history, science and ethics behind the decision of dropping the A-bomb, both online with alumni and offline in person. The scale and impact of the attack were confounding. Throughout the trip, I had been trying to see them from Japanese perspectives.

In Hiroshima and Nagasaki where the atomic bombs were dropped, I visited the atomic bomb museums and parks, and met with the survivors.

From melted lunchboxes to a watch that stopped at the moment of the explosion, the collection of artifacts was somber and evocative reminders of the destruction and loss suffered. Fountains were built as a symbolic offering for victims died of thirst.

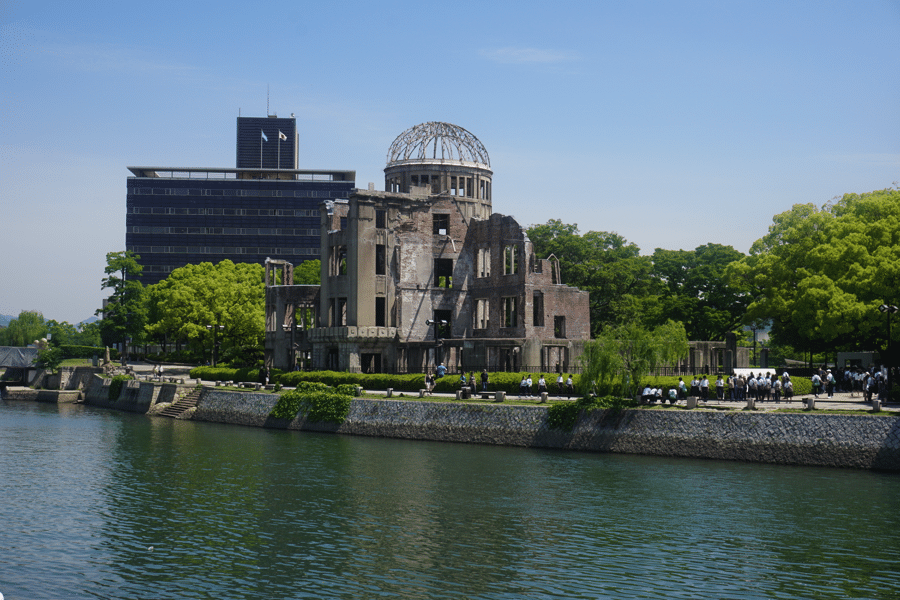

The Atomic Bomb Dome, which is one of the few structures left standing after the bombing, was a chilling symbol of the dark legacy of Hiroshima.

The atomic bomb dome left standing on the peaceful river bank.

At Shiroyama Elementary School in Nagasaki, newly constructed buildings stood side by side to the empty damaged ones. Students who were having lunch in the freshly-painted classrooms greeted us enthusiastically as we passed by, shouting “How are you? What’s your name?”. When I pictured the same innocent laughter from the damaged building 70 years ago in my head, it was such a depressing juxtaposition.

Both cities, because of their dark legacy, have devoted their human and capital resources to peace and anti-nuclear activism. Emerging from the horrific trauma seven decades ago, they also exude hope and life. Volunteers, many of whom have personal connections to the bombing, offer tours and presentation for visitors. On the riverbank alongside Hiroshima’s Peace Park, school bands performed an open concert, while school children in yellow hats hung strings of colorful paper cranes near the Children’s Peace Monument.

Cranes of hope – we folded 1000 and left them at the Monument

I think it is courageous that people found hope against all odds. I wondered how they overcame their personal loss, and came together as one again. When I asked a survivor from the Hiroshima bombing, about how he got over the psychological trauma, he chuckled, and fell into silence for a while. “ Life resumes. It was not good to look back. I had to look forward,” he said slowly and calmly.

It is also remarkable that the devastation of the past never overshadows the vitality of the present. While history has been remembered, people are not stuck in the past, but have moved on. Like the survivor from the Hiroshima bombing said, “history tend to be forgotten. It is important to learn from history and have facilities to tell the young about it. History is our mirror, we should forgive, but never forget.”

In Kyoto, the ancient capital, I saw a richer Japanese culture. In the Manhattan Project, Kyoto was identified as a potential target before the atomic bomb was dropped. However, with its sublime gardens, splendid shrines and state-of-the-art cuisines, it was no wonder that the Henry Stimson, the Secretary of the War, who had been to Kyoto, removed it from the list.

Besides visiting the famous temples, I went to a tea ceremony. While sipping the freshly prepared matcha, I marvelled at the exquisite cup in my hand. The temperature was just right. The taste was fragrantly fresh with a tinge of bitterness. Every movement of the yukata-cladded tea master was full of concentration and composure. It was Zen in a cup!

When I wandered in the Gion district, looking for geisha scurrying to their liaisons, I found brand-name boutiques side-by-side with traditional pastries and Japanese craft. When I strolled in the central shopping district in Shijo, I saw traditional tofu-makers, ceramic masters and umbrella makers who take so much pride in what they make, many of them original and unique. It dawned on me that if Kyoto were bombed, it is not just about Kyoto’s psyche, but the nation’s psyche – rooted in a rich collection of cultural monuments, ascetic discipline, and traditional practices, may be wiped out.

Wandering lanes in the dusk in Kyoto

We often use science as the solution, but irrevocably, it generates a slew of new problems. The problems today are never easy, and there might not be an answer. My visit to Japan has allowed me to better appreciate the dropping of the atomic bomb from the Japanese perspectives and has added more nuances to my understanding of the power of nuclear weapons and peace.

I have only scratched the surface, but it is a good start.