One of my favorite parts about my vacation home in America—other than demolishing a monstrous, seventy-two ounce whoopee pie with twenty of my friends from home—was that I was given a chance to deliver a talk on Xiangsheng and Chinese humor at a local arts center. My friend Stacy worked at the New Art Center in Newton, MA, and when she invited me to share what I’d been doing in China, I jumped at the chance.

When I started preparing, however, I found myself with an interesting conundrum. I knew from my time studying Xiangsheng that as my language and cultural knowledge expanded, I felt the pieces actually get funnier, in whatever subjective measure funniness is measured in. So how would I get the funniness of Xiangsheng across to an audience of my friends, family, and other local Bostonians, when they knew nothing about China, not to mention Chinese or Xiangsheng?

I decided the answer lay in stories.

Telling funny stories about how a friend of mine mis-pronounced the tones for “Giant Panda” at the zoo and asked me if I liked the “big chest hair” taught people about tones. Funny stories about a fellow member of my Xiangsheng troupe (accidentally) kicking a baby while playing soccer and having to take the kid to the hospital explained the idea of Xiangsheng and the troupe dynamics during my time there. And since modern, developing China is a madhouse—and I mean that lovingly; see any of my previous posts—just explaining my everyday life and experiences, as a C-list Chinese Internet celebrity is funny.

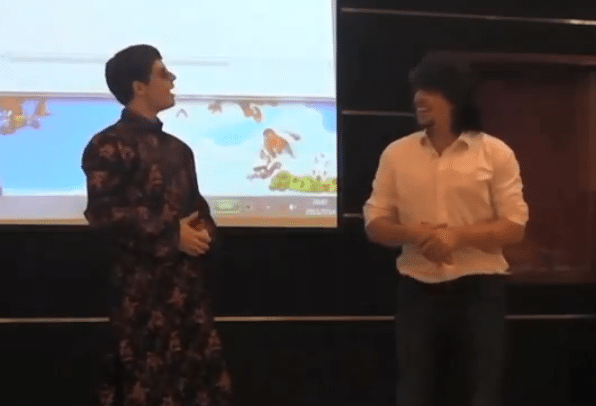

At one point, I decided to perform a short Xiangsheng piece, which I then translated. But because performing a piece about Zhou Yu from the Wu kingdom doesn’t ring many bells for most audience members, I also decided to translate the cultural tokens of the piece into Chinese—replacing the young general Zhou Yu with Joan of Arc, and so on. (I have another blog post that I will put up about translating Xiangsheng that goes further into this, but suffice to say for now that it was received very well, and might have done what I had hoped: to give people who speak no Chinese an idea of what listening to Xiangsheng is like.)

The result was pretty good, judging by the positive responses from an audience of about sixty. Even though the jokes people were laughing at were not “Xiangsheng” jokes, by being funny, I was able to keep a few dozen average Americans interested in learning about China, Chinese language, and Chinese culture for two hours.

I think this is the real value of learning Chinese comedy when applied in America: when people laugh, they invest themselves in the subject, and people are willing to learn about anything that can make them laugh. The dialogue on China in America is never on Chinese culture—almost always it’s debt, human rights, maybe ping-pong. But I think that’s not because Americans don’t want to learn about China, it’s just that nobody is explaining China in a way that’s funny. People don’t invest the energy. People don’t build the bridge, and they are wary to step over bridges that others—news media, for instance—build for them.

Laughter is a bridge, and the best part is that when you laugh, you build that bridge yourself. I was able to get people to laugh and learn about China, but the bridge they crossed wasn’t one I built, it was one they build themselves when they began to laugh. What they found on the other side was something they discovered themselves, and was much more meaningful for that.

And in the end, because each member of the audience wrought their own bridge with their own energy and their own interest, the connection will surely last longer, be stronger, and be more valuable.

PS: I recorded some of the talk, so keep an eye on www.laughbeijing.com for some clips that I will be putting up soon!