Last month, I went to a two-hour fascinating yet fastidious lecture about the role of Chinese language in shaping Chinese culture. It was hosted at one of my favorite cultural institutions in New York City – the China Institute. I did not invite friends. “Why not?” you may ask.

Well, it was on a Sunday – the first gorgeous Sunday in New York after Superstorm Sandy. Many of my Chinese-speaking friends are out biking or running in Central Park. And then – you may have guessed it: the two-hour long talk is a PowerPoint presentation in Mandarin Chinese.

Many New Yorkers would prefer a lighter Sunday activity like going to the movies, visiting a museum, going to the park or to the river than sitting indoors for a complex language lecture.

But to my surprise, the lecture room was packed. Most of the attendees are women dazzled by the intriguing topic of how traditional Chinese words, tone, shape, structure, sound of phrases & idioms affect Chinese culture.

At the very outset, the speaker, Professor Pan Wenguo (潘文國), clarifies what he means by “Chinese culture.” He said Chinese language (written words and spoken dialects) actually affects Chinese people’s “thinking” as reflected in their attitude, action, reaction. He listed several examples where Chinese words – when pronounced in Mandarin or Cantonese – sound like “death,” or “separating” or “leaving” are bad.

I’ve always understood how a Chinese word that sounds like “death” may suggest something ominous – something to avoid especially during Chinese holidays or festival. But I was somewhat struck by the idea that “separating” or “leaving” was culturally perceived to be a bad idea. To be clear, Professor Pan’s point about “separating” means leaving someone, or leaving a place.

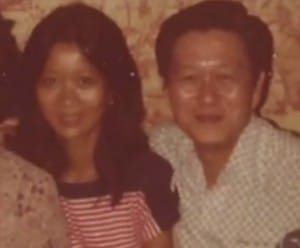

As I dug deep into my own understanding of traditional Chinese culture, I suddenly remember my father, now in his 80s. I remember how he once repeated this statement to me many times in his younger days, “I don’t like any of you leaving me. I want everyone to be close to me, all my children, grandchildren gathering around, and surrounding me.” My father would always end this statement with a big belly laugh.

What my father meant was that he did not like any of his children leaving him, he felt abandoned, left alone. All of us in the family know that well. My older brother, who is married with two grown children, lives next door to my father. And my younger sister also lives at home, taking on the role as a caregiver.

What my father meant was that he did not like any of his children leaving him, he felt abandoned, left alone. All of us in the family know that well. My older brother, who is married with two grown children, lives next door to my father. And my younger sister also lives at home, taking on the role as a caregiver.

I’ve always understood my father didn’t like to travel, or to exert himself to go places to explore the world. He’s never visited me in America, I’ve always gone back to see him and the rest of my family in Hong Kong. His mindset and sentiment reminds me of the traditional Chinese cultural psyche – one that stays firmly grounded to its roots, one that celebrates unity of family, one that scoffs at separation of family members.

On this Sunday afternoon when I thought I was to learn how Chinese language affects Chinese thinking, I learned something entirely different. I’ve re-discovered how incredible my father is, to let me leave him. A true gesture of love and let go. His deeply Chinese thinking expressed in words did not affect his action. He didn’t demand that I stay close to him. He didn’t make it tough for me to decide to live an independent life, following my dreams and my calling – wherever they lead me.

Perhaps that’s why I keep going back to visit him – at least twice a year. It’s my way of showing him I have never “left” him. I’m still very Chinese, and very American.

上个月我参加了一个时长两小时、非常精彩的,

好吧,讲座的时间是在一个星期天,

接下来发生的事你也许已经有了一些猜测。

时长两个小时的讲座是用中文,并以PowerPoint的形式进

许多纽约人在星期天宁愿去电影院、博物馆、公园或者河边,

但是令我意想不到的是,演讲厅里座无虚席。观众中很多是女性,

在一开始,主讲人潘文国教授澄清了他所理解的“中国文化”。

他列举了些例子,譬如在国语或者广东话中,当听到“死亡”,或者

我一直知道在中国语言中像“死”这一类的字眼可能意味着一些不吉

当我进一步思索着中国传统文化的博大精深时,

“我不希望你们中的任何一个离开我。我要你们都在我身边,

我父亲的意思是,他不愿意他的任何一个孩子离开他,

我一直知道我父亲他不喜欢旅行,或者背上行囊去世界各地探险。

这个星期天的下午,

也许这就是为什么我会经常回去看他,至少一年两次。