Pan Yabei is no stranger to poverty, overcrowding and the struggle to survive.

At age 16, he quit school and left his home village in central China’s poor and overcrowded Henan province. He traveled to Tibet to learn car repair. That didn’t work out. He trekked to Beijing on the newly-built Qinghai-railway, looking for work and a place to put down his roots. That paid off. He got a job as an express delivery worker (快遞服務). Soon, he jumped to work for one of the major carriers based at China Youth University in Beijing. Students there have money to buy anything they want online and return whatever they don’t want. They are a huge market for Pan’s company. Every day, he picks up, ships and delivers parcels to university students.

“These days, everyone has money. Their parents give them money.” Pan said with no trace of bitterness. That comment moved the Financial Times (FT) reporter who interviewed Pan for the article, to write -“Yet, he has every right to be bitter.” As I read on, I realize that Pan is one of thousands of other migrant workers in Beijing who has suffered under a massive eviction campaign.

The immediate cause was a fire in the slum district where they lived. That exposed the unauthorized housing arrangement besides the dangerously crammed and dilapidated living conditions. The migrant workers quickly became a target for the authorities to force out as they planned to cap Beijing’s population growth at 22 million by 2020. (2.17 million in 2017).

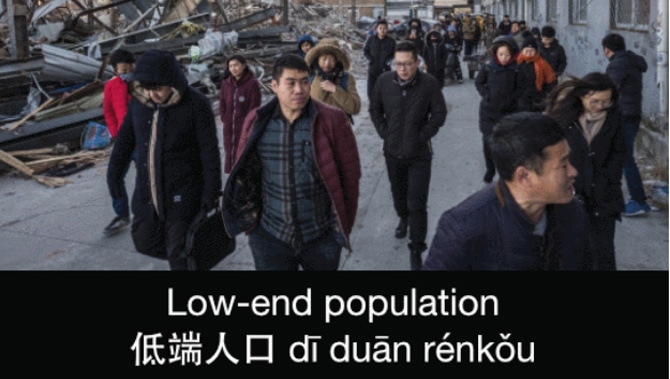

Last November, the government ordered a 40-day campaign to demolish these rickety housing complexes, and labeled the migrant workers who lived there as “low-end population.” That label “low-end population.” (低端人口) set off a firestorm of public outcry on social media chatter. Most are outraged for the degrading and dehumanizing language, asking “In Beijing Who Is and Isn’t a “Low-end Person?” They are outraged, sad and sympathetic. Some feel sorry for them.

*Image courtesy of http://www.scmp.com

What struck me most was how Pan chose to react. Pan may have every right to be bitter, but he refuses to feel like a victim. He won’t feel sorry for himself. He won’t accept food or clothing or money from university students – his clients. Instead, he focuses on what he has, and what he can do.

*Images courtesy of the Financial Times

- A friend who let him stay in a closet-sized room in an abandoned restaurant.

- His building has heat.

- A job that pays him a monthly salary at- a100,000 RMB ($19,000 USD) – on the par with the average monthly salary in Beijing.

- A dream – he plans to save enough money to return to his home village, buy property and retire.

- A strong mind and sweet smile. His incredible ability to “eat bitter” (吃苦) as the Chinese saying goes, reminds me of the Chinese character “忍” – “endure” in English which is the one Chinese word that we had to learn how to write over and over again as a child in elementary school. I had no idea why that was so important then, now I do. In the face of fast-changing circumstances that are out of one’s control, that “endure” concept has served me well. It helps me focus on what I can do. In Pan’s case, with just a few days’ notice, before he had to move out, he did not crack.

He focused on who can help him with his most urgent need. When asked how he felt about this swift and cruel eviction, his smile faded. He said it wiped out his years of hard work trying to adjust to a new place, it told him he didn’t belong here. If not here, where? Pan is no stranger to struggle. He goes find another way. Feeling bitter is not his way. He keeps his focus on what he has and what he can do. He is my new hero.