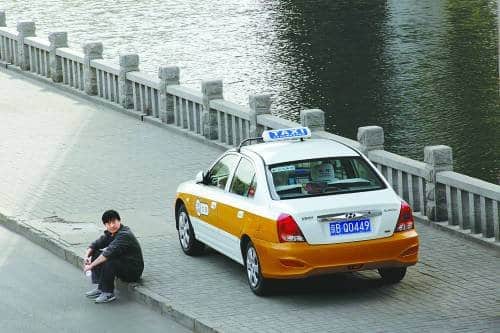

I was in a cab to the airport leaving Beijing, and my conversation with the cab driver turned from politics to education.

(From Part 1: “When I was growing up, life as a kid was easy—the system was that you would take over your father’s occupation once he retired. So life was easy and carefree for us kids. We have a few fights and throw a few rocks. There wasn’t a lot to worry about, even though things were tough.”)

“Today’s society is even more about 人脈 (euphemistically translated as “human capital”, pessimistically “who’s your uncle and aunty”),” the driver continued.

This I had to question:

“The Chinese education was and has been the tool for social mobility. Nowadays there are signs up encouraging 民工 (migrant workers from smaller cities or rural areas) to take up further education that’s funded by the government. So education is still very important, no?”

“Today’s education isn’t about education. It’s about passing an examination; it’s about being better at taking exams than everyone else. And most teachers today couldn’t care less about you unless you sit in the front row and rank top in the class. After class, they are gone. The teachers in my day taught you everything they knew.”

This was powerful, but not entirely true. My time at Peking University, the honor of Chinese families, and the 0.00001% of the student population showed me that here at least, there were teachers who considered examinations almost as an afterthought, merely a demonstration that you attended the classes. I’ve met teachers who did try to teach you everything they knew (such as how to be a good person), who considered their wisdom and knowledge a responsibility to pass on.

He went further.

“The effect of such an educational system is competition on a neurotic level. The other day I read in the news about a kid who was an excellent student. After graduating with a PHD he returned home to become a secretary to a provincial vice minister. The minister took a liking to the kid, and he began to trust the kid more and more,” he paused as a black Audi pulled across our lane without any signal, “but after three years they found out he had embezzled 5 million yuan through a hundred tiny transactions.”

I questioned the obvious, “This is the effects of intense competition from a young age? So someone who has succeeded by outside observers—“

“Yes—“ he cut in.

“—when you are young you can always work harder to get ahead in grades, but in society, working harder sometimes is only a long route—“, we were onto something here, I felt.

“He might look around and see other people with more, with better, and his innate drive, the thing that took him to where he was after graduation, coerced him to acquire more, acquire better,” the driver said.

Whilst what he said had merits, only a subsection of high achievers walk down that road of corruption. Certainly, most did not. He might have referred to the anomalies of these institutions, starting with the schooling system, which might have a tendency to produce these types of individuals.

I might be out of Beijing for a while, but I certainly will return. As long as the taxi drivers still tell it like how they see it then, things can only improve.