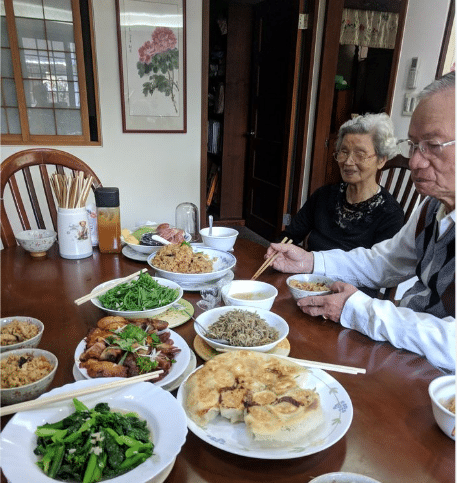

My grandmother’s dining table is never empty. You will always find a canister of chopsticks, a plate of sliced guavas and wax apples, and a pot of bamboo soup leftover from lunch, waiting to be reheated for dinner.

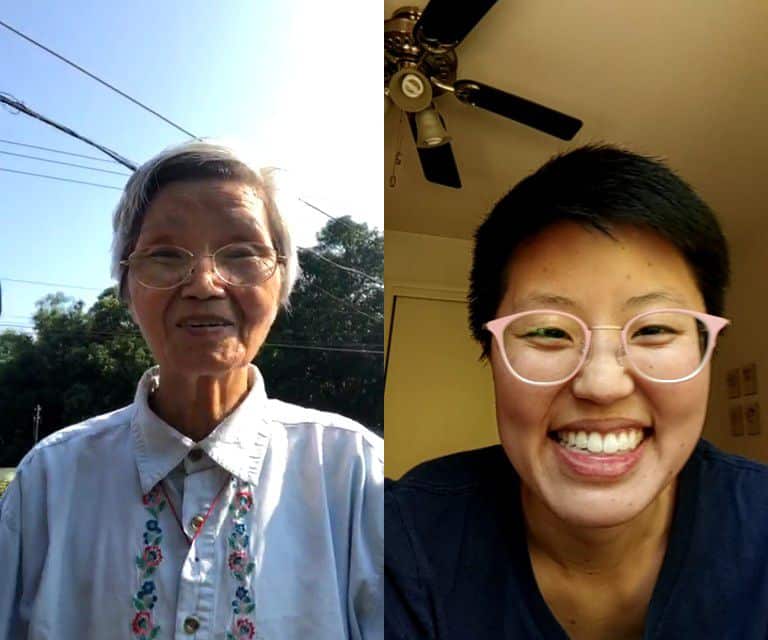

Like many other children of the Chinese diaspora, I am separated from my grandmother by four languages, three generations, and two continents. Sometimes, the distance between us feels impossible to bridge.

But the one thing that connects me to my grandmother is her food. It’s a substitute for the conversations we can’t have. It’s a way of understanding each other, despite our different cultural backgrounds.

Food plays a similar role in the new film, The Farewell, directed and written by Lulu Wang. The film follows Chinese American Billi — portrayed exquisitely by rapper Awkwafina — as she grapples with her family’s seemingly absurd decision to withhold a terminal diagnosis from Billi’s grandmother, Nai Nai.

Rather than potentially hasten Nai Nai’s death with bad news, Billi’s family orchestrates a shotgun wedding for Billi’s cousin, an elaborate charade to bring everyone together for one last gathering with Nai Nai.

Throughout The Farewell, food is omnipresent. It shows how Chinese families live and spend time together, clustered around lacquer dining tables laden with bowls of dried red dates, melon seeds, and sesame candy.

It also shows how Chinese families like mine think, feel and express themselves.

My grandmother was born into poverty in 1930s Taiwan under Japanese rule. She never received more than an elementary school education and was the only daughter not given away in marriage at a young age.

My grandmother entered adulthood just as the island came under martial law. Family lore has it that she chased away armed Chinese soldiers stealing fruit from her family’s subsistence farm by pelting them with pomelos.

Years of hard work and manual labor have bent my grandmother into a bundle of frustrated energy. She has had both of her knees replaced, but her arthritic hands still busy themselves hacking the tough skin off massive bamboo shoots, and stringing up elaborate melon trellises in her garden.

When I picture my grandmother, she is slicing fruit, peeling vegetables, stir-frying another fragrant dish.

She speaks through her food — especially during my visits to her home in Taipei.

The plate of cut fruit that greets me after a 14-hour flight says, “Welcome home.” The shiitake-studded chawanmushi, an egg dish she makes for breakfast, says, “I’ve missed you terribly, and want to hear about your life.” Her sticky rice, stewed pork and stir-fried greens say, “Eat up because I want you to be strong and healthy.”

I eat everything she gives me. And then I eat more than I want until I feel sick. Because that’s the only way I can say, “I’ve missed you, too, and I’m sorry that I haven’t visited.”

“I’m sorry that I can’t say this with my own words.”

There’s a scene in The Farewell that feels like it was taken straight from my relationship with my grandmother.

In it, Billi takes a bite out of a meat pie offered by Nai Nai with her own chopsticks. The look on Billi’s face says that she feels infantilized — since only children are fed by adults. She feels guilty for not telling Nai Nai the truth, and she can barely eat because she’s grieving.

But Billi accepts the food anyway because it’s all she can do.

“You swallow the food along with your feelings,” Wang says. “[You swallow it] along with your grief, along with the things that should be said that aren’t said.”

In many Chinese families, words are eschewed for actions. Whenever I visit my grandmother’s house, I bring a box of red bean mochi or some other little snack, a gesture that shows I was thinking of her while I was away.

The act of giving rather than receiving is echoed in a scene of The Farewell, where Nai Nai encourages the family gathered around her, “duo chi yi dian!” or “eat up!” Rather than comply, the family members sitting closest to Nai Nai leap to their feet and try to shove food onto her plate instead.

It’s their way of saying, “No, I love you more,” even though it’s the exact opposite of what Nai Nai requested.

This back-and-forth is a ritual that binds people together across generations and distances. But “it can often feel overwhelming and oppressive,” Wang says. “Because it’s like, what are we trying to fill with all this food?”

I wonder that, too.

The delicate balance between cultures that Wang portrays in The Farewell is what makes it resonate so much with second-generation Americans like me.

“I’ve always had to negotiate between my American identity and my Chinese identity,” Wang said on a recent episode of Evan Kleiman’s “Good Food” podcast. “When I told my parents about [The Farewell], my mother would say, ‘How can you make this film, you don’t understand China!’ And it’s almost like, ‘Do I not have a story? Am I not allowed my perspective?'”

I was born and raised in the U.S., and when I was a child my family would visit Taiwan once a year. But as I grew older, my education and career got in the way. Now, trips to my ancestral homeland are too sporadic — once every couple of years, at most. Now, visiting my grandmother feels different.

When I go back to Taiwan, I am never hungry. I am constantly giving and accepting food, and it feels like I am being force-fed love with each bite.

And yet, when I am in the U.S., I have a strange, bottomless hunger. I have gone six weeks in Texas without eating a bite of barbecue, simply because when my stomach grumbles, my homesick heart drives me to yet another Taiwanese noodle soup joint where, inevitably, the soup never tastes quite like home.

Sometimes it feels like this hunger, this distance between my grandmother and me, is too great.

But The Farewell gives me hope, because it’s not just a story about a family that shoves food at its problems and each other.

It’s also a careful depiction of how relationships can change, and what’s gained from that change. There is no explicit moral to the story, no feel-good resolution by the end of the film. And yet, it’s clear that Billi gains a new understanding about her family, and about herself. An American film set in China, The Farewell is, like its creator, a hybrid that is greater than the sum of its parts.

The film has a Chinese title that conveys a slightly different meaning than The Farewell. Wang worried that the literal translation, Gao Bie, felt “more literal in Chinese,” Wang says. “It felt too heavy.”

So she enlisted her mother to help come up with the Chinese title, Bie Gao Su Ta, which translates to Don’t Tell Her.

The two titles felt like a secret note assuring me that I wasn’t alone in my strange hunger. That there are others who also feel like they are in between worlds. That we are all trying to close the distance within our families.

And so, The Farewell feels like a promise: That one day, I, too, might find comfort at my grandmother’s table.

This blog is published with permission from Irena-Fisher Hwang, to read more blogs by Irena, click here.