“At some point in your life, it could be after you are retired, it could be at any time at all, you will ask yourself the three basic questions every security guard has asked of you:

Who are you?

Where are you from?

Where are you going?”

It was the last Classical Chinese class of the semester.

Our teacher, Shao Yonghai, spoke at length on the topic he began the semester with: why we learn Classical Chinese. It was an expression of the inklings that our hearts knew but had no words to voice. It was the final confirmation that this semester’s learning would not fade as others have.

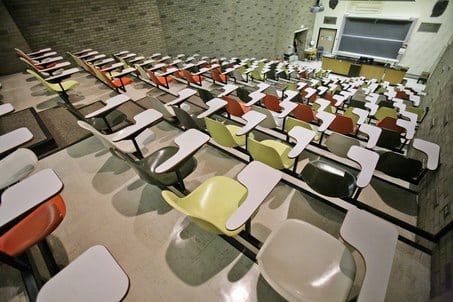

I sat with John Carlyle, the only other exchange student in the class, at the far end of the first aisle in the cement floored lecture room. White chalk popped out on the double blackboards, the fierce Beijing northwesterly rattling the thin wooden framed windows behind heavy stained curtains.

The class is compulsory for students majoring in Chinese, aiming to improve their ability to independently read Chinese texts dating from the Spring Autumn-Warring period (approximately taking place from 771 BC to 476 BC). This is the period that spawned Confucius, Mencius, Laozi: the birth of Chinese philosophy and thought that is the backbone of Chinese tradition today, including much of East Asia.

I’ll paraphrase a few selections in English (any errors are entirely mine):

“As a latecomer to any game, we can only learn about the rules of the game, hoping to understand them as best as we can. To stay and thrive in the game, the latecomer must emulate the game rules, and use them as best he can. His success is determined by the standards set by the game masters. Under such a condition, China will forever be a second class player.”

Our teacher might have been referring to China’s lack of soft cultural power on the world stage, or its inability to regenerate its own authentic culture in the current political climate. He defined “cultural authenticity” (文化原创) as, “how people view, interpret, and interact to universal phenomena” (人对宇宙的现象的解释,参与,彼此的关系).

We cannot do such a thing honestly without understanding how those who saw these things before us did. And the only way to do that is to read their words for ourselves, not through someone else’s lens.

It’s safe to say that our teacher missed the invitation to the “10th Forum on Cultural Innovation Strategy: Creativity, Science, and Technology,” held recently at Peking University (click here for highlights of the 9th forum).

Then the teacher turned to us:

“For those of you who will use another language overseas, for professional purposes as a tool, or as a language of communication, even if you predominantly use this language, Chinese will remain your mother tongue. Whether you wish this or not, this will happen. At that time, you will reflect, and you will wonder how your forefathers dealt with these questions before you. When you do, your ability to read for yourself and interpret these answers will be called into question, and at this time, you will long to immerse yourself in your mother tongue again.”

Our teacher described what I had found. What did not reveal itself to me until I sat in on his class at the start of semester, until I began learning the tools to enter this world. One piece of homework speaks volumes for his tutorage: write a letter to your parents about back home, in classical Chinese (文言文).

John and I were left in awe of our teacher’s speech, the sincerity with which he spoke, the honesty felt deep down in our hearts. He struck the core of our journey to China.

We are privileged to call him our teacher.

在将来的某个时刻,可能是你退休之后,也可能是其他任何时候,

你是谁?

你从哪里来?

你要去哪里?

这是我们上节文言文课讲的内容。

我们的邵勇海老师在最后的时候说了这学期的学习话题 “我们为什么学文言文”。这是我们心知肚明,

我与班上唯一的交换学生约翰卡莱尔,

作为中文专业的必修课,

在这里我用英语引用一些他们的经典名言(如有误,敬请谅解):

“作为游戏中后来者,我们只能学习游戏规则并尽可能理解他们。

我们的老师也许说到中国在世界舞台上缺少软文化实力,

如果我们不能理解先人如何看待这些,

我们的老师很遗憾的错过了近日在北京大学举办的第十届文化创新战

他跟大家说:

对于你们这些要在其他国家讲外语的同学来说,

我认识到的老师在课上讲了,

约翰和我都被老师的发自内心的真挚情感演讲所打动,

能做他的学生,余有幸焉。